“Wind extinguishes a candle and energizes fire. Likewise, with randomness, uncertainty, chaos: you want to use them, not hide from them. You want to be the fire and wish for the wind. “

Prologue, Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

I recently worked on a project to design the new Aragon delegated voting DAO. By the end of it, I was looking at DAOs in a completely different way. (In a good way.)

Today, I’m going to share what that new viewpoint is. If you’re new-ish in crypto (like me) it might surprise you. If you’re an OG, you’ll probably say this is how DAOs were meant to be all along.

The task my team worked on—designing the basic structure of a delegated voting DAO for Aragon—quickly pivoted into undesigning a DAO, or taking pieces of our draft away until we had the most basic, bare bones approach possible.

This was completely different from how I’d expected the DAO design to go. I imagined an airtight proposal process and delegates with clear rules on what they can and cannot do. I imagined codes of conduct, set definitions of guilds vs. workstreams vs. contributors, and required reporting standards. I imagined us outlining all the things that we’ve seen go wrong in DAOs, and then creating a robust framework to combat that. DAOs are complicated, so we make a complicated design, right? To protect against attackers we need to think through every possible scenario and design every inch of the organization to be completely spotless, right?

Nope.

We trimmed it down, then trimmed it down, then trimmed it down again, until the design was so basic it looked like we could’ve written it in a half a day (try half a year). We trimmed and trimmed because we realized something important: antifragile is better than robust. Aligned incentives are better than hard-and-fast rules. Lean and simple is better than large and complicated.

Let me show you what I mean.

The sliding scale of organizations

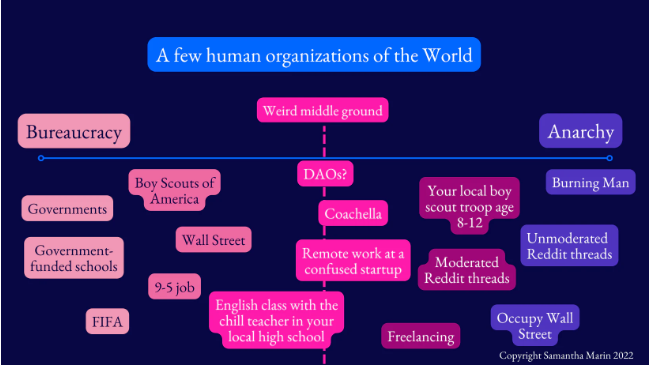

When designing a DAO, you’re constantly walking the line between two extremes. On one side, you can set up tons of social layer rules with managers enforcing them in a bureaucracy. Or, you can set up zero rules and zero boundaries, ending up in anarchy.

All organizations of humanity are sliding between bureaucracy and anarchy. Some are happily planted on one side of the scale, while others are fighting to not slide too far in one direction. Here are a few organizations of the world and where I believe they land on the sliding scale:

One major goal when designing a DAO is to not land into one of those two extremes. But…honestly? The weird middle ground isn’t so great, either, because no one’s figured out how to do it right.

Everyone theoretically wants to be somewhere in the middle (bureaucracy and anarchy both sound bad), but landing in the middle is not easy.

And, what I learned from the DAO design process is that the organizations that land in the middle are kind of….off. Just look at the chart above: everything in the exact center is a slightly off version of something else.

DAOs in their current state are no exception. Populist social DAOs with open Discords are a middle-ground version of anarchy. Highly-regulated DAOs trying to enforce rules on the social layer are a middle-ground version of traditional companies.

We didn’t want to fall into either of those two options.

DAOs don’t need to be a slightly off version of something else. DAOs can turn into something new and innovative and exciting. But for that to happen, we need to stop trying to enforce things we can’t, brute-force shifting ourselves on the sliding scale, or designing when we should be undesigning.

The pull of bureaucracy is dangerously strong

During the multi-month process of designing this DAO, I found myself continuously falling back into the bureaucracy trap. I kept wanting to add more rules and to design more parameters to hem this DAO in place. I kept thinking of a new issue and saying, do we need a solution for this? Shouldn’t we put a rule in place so no one does it?

But rules don’t mean anything if you don’t have enforcement behind them. And as soon as you have enforcement, you have bureaucracy, managers, and the old system we’re trying to opt out of.

Links, member of BanklessDAO, wrote his insights from serving on the Grants Committee, the board that distributes funding to projects every season.

“Rules without enforcement aren’t worth the blocks on which they are minted. Writing down rules and hoping individuals follow them doesn’t lead to a post-scarcity nirvana, it leads to people breaking rules (often without realizing it). For rules to work, you need a central authority which is enforcing them.”

—Creating a winnable game by Links, published in the BanklessDAO Weekly Rollup

We all know the spiral: Bob steals the office stapler, so HR freaks out and puts a rule in place against stealing the office stapler. But there’s no rule against bending the office paper clips, so Alice bends them to better fit her massive stacks of paper. A sales manager puts a rule in place for the sales team against bending paperclips. But there’s no rule against bending the stapler, and the two rules live in totally different places, so Bob gets a crowbar to see if that’s possible. And on and on. This happens until there are so many rules in place that the organization needs to hire a whole department just to keep up with the rules. But you need to make sure the new Office Rules department isn’t bending the staplers with the crowbar, so an oversight committee is placed over that.

This goes on and on until you can barely find a productive organization through all the weeds.

We were scared of going too far toward bureaucracy, making it cumbersome and slow to get things done. But we were also scared of falling into anarchy, where the treasury could be drained into the hands of attackers and non-mission-aligned projects.

Our solution: being crystal-clear on our limitations of enforcement (very, very limited), and letting ANT (the governance token) govern the rest.

Defining what we can and can’t enforce was central to our design

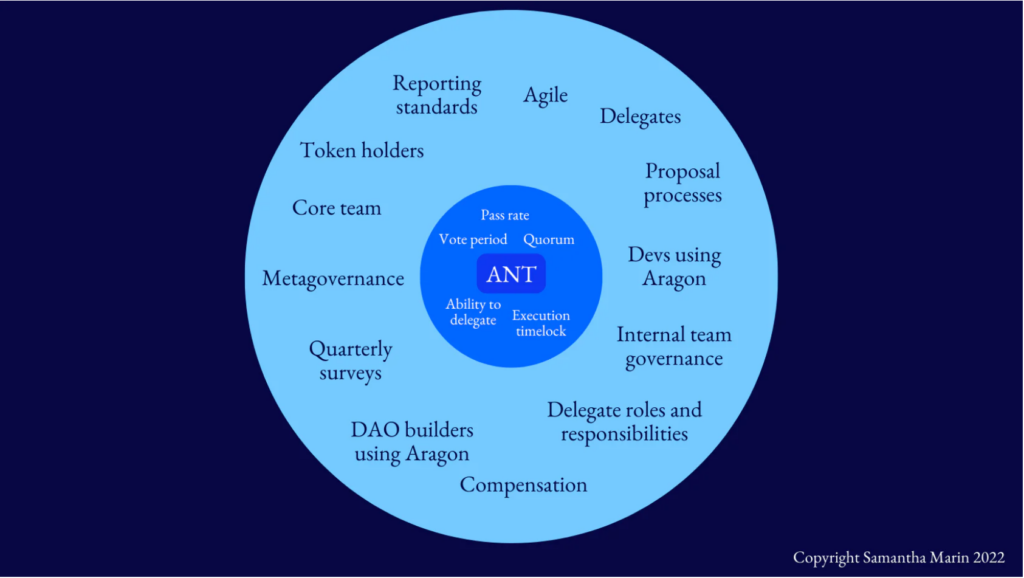

In the new Aragon DAO, $ANT (Aragon Network Token) is at the center. ANT votes—not whales, not delegates, not the core team, not the community. The tokens vote, so we design the DAO to place the tokens at the center, not to place a certain group of people at the center. (This was particularly hard for me to wrap my head around, so I’ll keep explaining it further.)

Part of the point of a DAO is that if the core team quits tomorrow, the organization can continue functioning because it’s both decentralized and autonomous. However, this is not the case for most DAOs today. But we want this to be the case for Aragon. A DAO that puts a specific set of people at the center rather than the tokens and the code cannot live up to that ideal.

So, we put tokens at the center by designing enforceable, on-chain rules for tokens—the parameters the tokens need to meet like quorum and pass rate—but no enforceable rules for anyone else. This was done to avoid the strong pull of bureaucracy and to put ANT at the center.

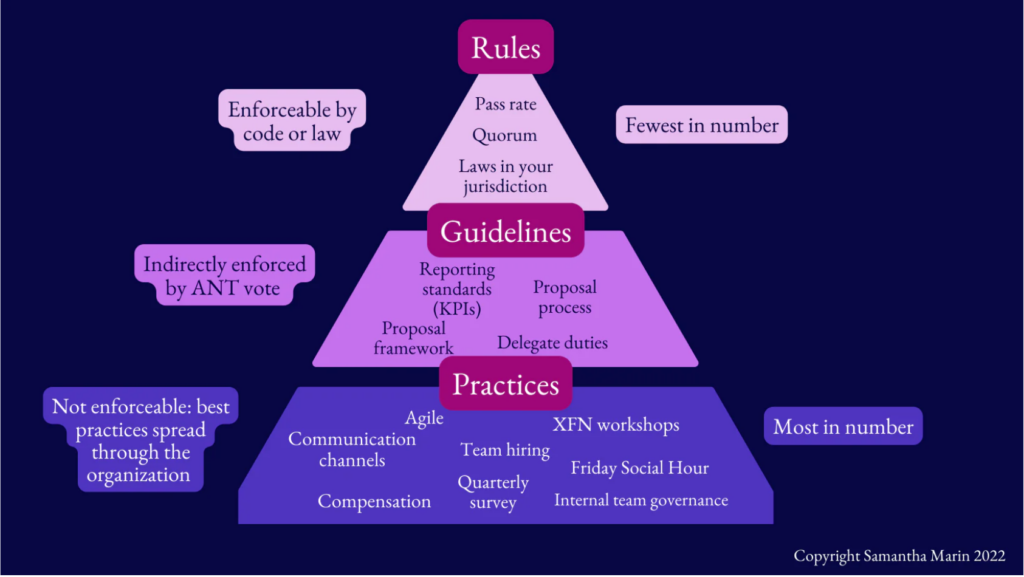

Here’s our three-pronged approach to describe the layers of Aragon governance:

- Rules: Enforceable by code or law. Things like quorum and pass rate (parameters in the smart contract) as well as any legal restrictions for the legal wrapper you’re operating in (illegal to launder money or fund terrorism with your guild’s treasury, for example).

- Guidelines: Standards that help us coordinate better as an organization that are not technically enforceable by anything, except by how ANT votes. For example, if there is a guideline to include team member backgrounds and relevant experience in each funding proposal, ANT could theoretically only vote “yes” for proposals that include the description. However, there’s no one chasing the proposal writer around saying, “You need to include this or else your proposal is void!” If the majority of ANT don’t care if the proposer followed the proposal guidline, then it doesn’t matter. Because ANT is at the center. (I’m going to keep drilling that in because it really did take me months to wrap my head around.)

- Practices: Ways of working that spread to other teams, such as meeting styles, compensation standards, and anything part of an organization’s operating system. Practices are not enforced, rather the best ones are spread throughout the organization when a successful one catches on.

We stacked it up into a layer cake or triangle, like this:

More simply, you can break the design into what’s at the center vs. what’s pushed to the edges. ANT is at the center, and everything in dark blue is tied directly to ANT, restricting its action (for example, 1 ANT cannot pass a proposal, you need at least a certain percentage of the network). The black text in the light blue outer circle is everything that’s pushed to the edges.

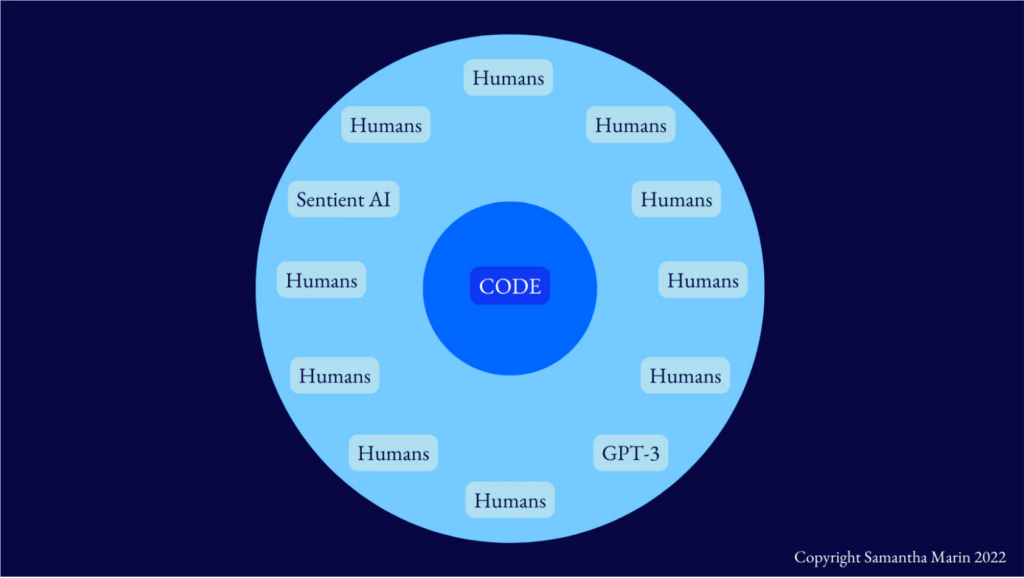

Or even more simply, like this:

And suddenly, we’ve arrived here:

“DAOs == automation at the center, humans at the edges.”

—Vitalik Buterin, DAOs, DACs, DAs and More: An Incomplete Terminology Guide

Why is this design antifragile?

A fragile organization is one that needs everything to work exactly how it was designed. A machine is fragile: if one part breaks, the whole thing crumbles. But an antifragile system gains from disorder. A forest is antifragile, because even the occasional natural forest fire is regenerative and restorative to the ecosystem.

Our system is antifragile because the Rules at the center are unstoppable and secure. When a proposal is voted through, on-chain execution ensures it is passed. The Rules are airtight.

But the areas that don’t need to be airtight—the human layer—are free for more experimentation, more adaptation, and more trial-and-error. Putting humans at the edges makes us even more antifragile because we can test safely without high stakes looming over us. Without some failures, we’ll never be able to find the best solution.

We don’t want failures on the Rules level. But we do want healthy failures on the Guidelines and Practices level to help us improve as an organization.

In other words, we need to become the fire, and not fear the wind. We need to not only last through the wind, but to wish for it.