This essay is to attempt to explore ways to understand how digital and decentralized identity will evolve over the coming years, by examining the interplay between the various forces that shape it using a socio-ecological framework.

As our transition to a more digital society continues, what will this look like from the individual’s perspective, and to what extent will the individual have any agency in how their digital identity is manifested?

The reason I chose to write this essay is because this is a question that has come up in a number of conversations recently. It is a question I’ve been trying to think about, and I have found it particularly challenging. Most of what I’ve written for this essay has been deleted, re-written, and deleted again. I’ve applied various models to try to understand how the various aspects and concerns of digital identity relate to each other. I began to think that the very concept of digital identity is just too broad, because digital identity is related so closely to individual identity, which itself is an unfathomably complex topic, and made more complex by the fact that identity technology is continually evolving.

If part of the complexity of understanding digital identity is the intrinsic relationship to an individual’s identity, then perhaps we need to borrow tools from fields of research in the social sciences that have already explored this subject in depth.

Applying a Socio-ecological Model

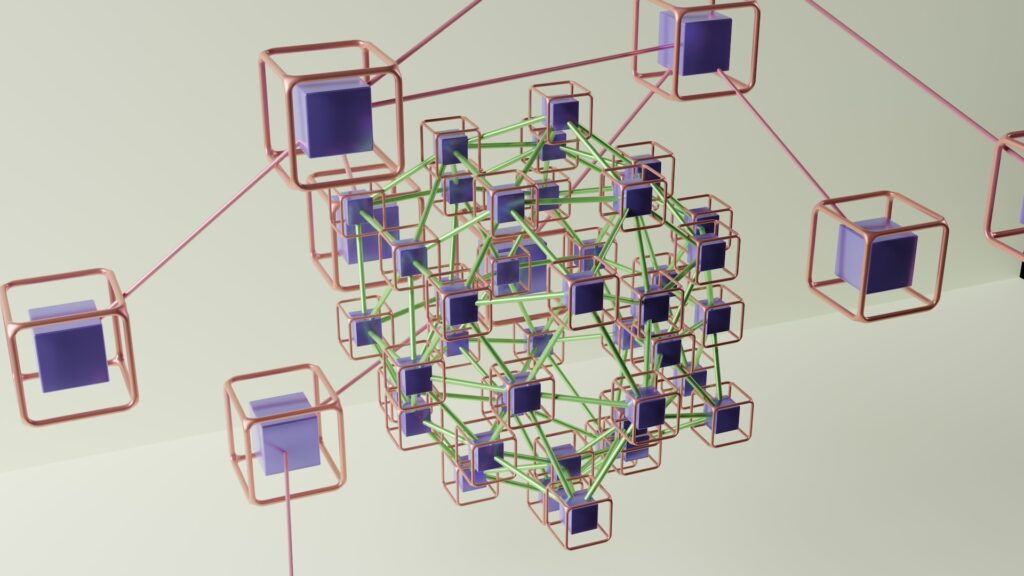

Ecological models are derived from systems-theory, which examines how the various discrete elements within a system are related and are interdependent. Socio-ecological models are frameworks for understanding the ever-changing interplay between various individual and environmental factors.

One such socio-ecological model is Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Framework for Human Development [1]. This framework attempts to understand how a person develops in the context of their environment, or rather the entire socio-ecological system to which they belong.

This sounds like the sort of framework that can be used to start structuring the complex topic of digital identity in order to get a sense of what it might look like from an individual’s perspective over the coming years.

Bronfenbrenner’s model consists of five nested subsystems that each affect an individual’s development, and each subsystem influences, and is influenced by, the next nearest inner and outer subsystem. These five subsystems, or levels of influence, are as follows:

- The microsystem is the subsystem that is closest to the individual. In the original model this would be family and peers, and in terms of digital identity, it would include the individual’s interactions with their personal devices and online accounts and/or wallets.

- The mesosystem is a layer in which we find two or more connections between elements of the microsystem. In digital identity terms, we would consider the connections and relationships between the individual’s devices and accounts and wallets.

- The exosystem contains various structures that affect the individual, but in which the individual does not directly participate. In identity terms, we would consider technology trends or market dynamics that may affect product features or privacy policies.

- The macrosystem defines the larger political and cultural context in which the individual exists, and structures in this layer have a cascading influence on the relationships between entities and structures on all other layers. In terms of digital identity we would consider the global political and economic systems that shape the development and implementation of decentralized identity technologies, and we might also consider broader societal and cultural norms and values surrounding identity and online behavior.

Using this model, we can begin to develop a framework for understanding what digital and decentralized identity will look like from an individual’s perspective as it evolves over the coming years, by examining how the various structures in each subsystem interact with each other and the individual.

Microsystem

The microsystem is the system that is closest to the individual and represents their immediate environment. From an individual’s perspective, there are several trends that may emerge that define how a user interacts with both in their online environment and with their local environment, using their personal devices, wallets and online accounts.

One such possible emerging trend is that we may see increased network effects of the incumbent big tech companies such Google, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft, who will continue to increase their custody of our data, and will accrue more influence over how we manage our digital identity.

Conversely, we may also see an emerging trend towards the adoption of decentralized identity technology, which allows for more privacy, control, and self-custody.

Web2 Wallets

Both Apple and Google have ostensibly started re-appropriating the concept of a “wallet” from web3, and have started slowly pivoting from the Apple Pay and Google Pay solutions, which allow users to make contactless payments, to a more general purpose “wallet” feature, that allows for a wider range of use cases.

Apple Wallet for example allows users to carry their driver’s licenses and state IDs in several states in the USA, and allows for storing transit tickets, show tickets, flight boarding passes, as well as employee or student ids, vaccination records, and even house and car keys.

This is the vision of an open identity wallet, but without the openness. Apple seem to have eschewed the use of open standards such as Verified Credentials and Decentralized Identifiers, and have instead opted for proprietary protocols, with the exception of support for the ISO-18013–5 mdL Mobile Driver’s License specification for driver’s licenses, though this may have been prompted more by certain state’s policies more than a willingness to embrace open standards.

In an almost identical move, Google has started transforming its Google Pay feature to Google Wallet. It will have largely the same features as Apple Wallet in as far as it functions as a general purpose “credential wallet” for storing tickets, identity documents, membership cards, boarding passes etc. Similar to Apple Wallet, Google Wallet is not built on open standards.

It will be interesting to see if the adoption of these wallet apps by the general public will pave the way for alternatives that are based on open and interoperable standards to come to prominence. It is reasonable to assume that once the concept of a “credential wallet” gains widespread adoption, that there will be a market for alternatives, including potentially web3 wallets, if they can offer at least an approximate level of functionality and convenience, and also find a way to counter the network effects of big tech.

European Identity Wallet

In June of 2021, the European Commission published a proposal for a European Identity Wallet. The proposal states that very large platforms will be required to accept the use of European Digital Identity wallets upon request of the user. According to the proposal:

“Under the new Regulation, Member States will offer citizens and businesses digital wallets that will be able to link their national digital identities with proof of other personal attributes (e.g. driving license, diplomas, bank account).”

This would obviously be a huge boon for digital identity, and decentralized identity. With the availability of mobile enabled identity wallets, and the requirement that “very large platforms” must support the use of these wallets, millions of users will become familiar with the concept of using wallets for managing digital credentials.

This initiative may help to normalize the idea of a “credential wallet” or “identity wallet”. This in turn will hopefully drive more adoption of open-source self-custodial web3 wallets, and encourage more issuers to issue wallet-agnostic credentials based on open, interoperable standards.

Web3 Wallets

Web3 wallets are themselves continually evolving and becoming easier to use. Many of the primitives that web3 natives take for granted such as the ubiquitous “secret recovery phrase”, or the UX around setting transaction fees, can be hard to grasp concepts for the crypto curious, and this has proven to be a barrier for adoption. A number of wallets designs have appeared that allow for easier onboarding and progressive self custody. Some of these designs include features such as “seedless setup” that rely on the social recovery features of smart contract wallets, or leverage MPC. See Magic as an example of a wallet that provides easier onboarding. Other wallets go further and abstract away transaction fees entirely for certain use cases, such as Unipass for example.

What remains to be seen is whether Web2 wallets and Web3 wallets will ever attain approximate feature parity, or whether they will diverge and remain different applications entirely. Will Web3 wallets begin supporting Verifiable Credentials and other formats such as ISO-18013–5 mdL for example? Will Web2 wallets ever support self-custody of digital assets?

From the individual’s perspective

If successful, this European Identity Wallet should pave the way for a huge reduction in cumbersome bureaucracy and should allow users to safely transport their identity across borders. It should see an end to printing out a form, filling it out in black ink, and then seeking notarization from some official, only to bring it to a government department so that they can laboriously type it into some siloed IT system.

If more issuers of credentials decide to support Apple and Google Wallets, it will make everyday interactions within the individual’s immediate environment seamless and frictionless. Presenting a ticket for public transport or parking, availing of student or OAP discounts, accessing a gym or borrowing books from a library (both of which require proof of membership), or accruing and spending loyalty points, will be almost invisible processes.

Whether this leads to more surveillance and influence by big tech and governments or more control to the individual depends in part on higher levels of influence.

Mesosystem

The Mesosystem is the layer in which structures within the microsystem interact with each other directly, which in turn has an effect on the individual.

If we think about digital and decentralized identity in these terms, some key trends start to emerge, including interactions between our existing online accounts and Identity Providers such as Google and Facebook etc., but also in terms of how our on-chain addresses and associated on-chain histories begin to interact with each other.

If network effects continue to drive widespread adoption of solutions offered by Apple and Google etc. then we will likely continue to see the extension of the federated approach to identity management that we are now used to. In this model, we are granting permission, through an Identity Provider (Google, Facebook etc.), to allow some third party applications to access our data. In this model, the IDP facilitates the authentication and sharing of data, and our interaction with the platform or application of our choosing is dependent on this facilitation. The more that digital identity evolves past authentication and sharing account data, the more that big tech companies occupy the mesosystem.

What does it mean for the individual?

From an individual’s perspective, this can involve interactions between online accounts, such as an account with some financial services company and an account with a KYC company. While this interaction currently cannot happen without the individual’s consent, the influence of structures within the Macrosystem such as legislation governing KYC/AML, mean that individuals effectively have no choice but to consent. The same type of interactions between online accounts can be seen occurring between accounts related to health, banking, employment as well as finance. While the individual is usually required to give consent to these interactions, more often than not they are at a disadvantage if they don’t.

Web3 Mesosystem

In web3, the mesosystem defines the various interactions between DAO memberships, reputation scoring or credit scoring protocols, airdrop eligibility etc.

To illustrate what this means with some examples……

KYC/AML, Accredited Investors

Decentralized insurance provider Nexus Mutual requires a simple KYC process for its users, in order to whitelist their Ethereum address; this enables lower insurance premiums by reducing perceived counterparty risk to underwriters. Decentralized Lending platform Goldfinch allows users to take out under collateralized loans, by requiring users to undergo a KYC process to obtain a “Unique Identifier”, in the form of an erc-1155 NFT. Sushiswap announced support for franchised pools, which will allow institutions to set the parameters for participation for liquidity providers and traders, and other examples include Aave Arc, Compound Treasury, or Verite by Circle.

Reputation Systems

There are various protocols which offer reputation systems for web3, that index on-chain data for a given address, supplemented with other off-chain records associated with that address, and combined to create a reputation score that can be used by dapps and smart contracts. Examples of such reputation systems could include protocols such as Omnid or Orange Protocol for example. The on-chain activity they index can include things such as:

- Funding a Gticoin grant

- Total debt on Aave, health factor etc.

- Participation in various DAOs

- Number of POAPs minted

It is envisioned that these reputation protocols will be used by dapps to understand their user profiles better. This could have uses for DeFI dapps and DAOs to understand more about their members, and what other dapps their customers are using as well, and could have huge benefits for how DAOs are governed, or making access to credit more accessible.

These protocols are very powerful tools that can have huge benefits, but it all depends on the vigilance of each of us as builders and co-creators of web3. These tools can inadvertently create a Mesosystem that impedes an individual’s growth and development.

A note on Negative Reputation

Reputation can be built through on-chain activity, as well as through attestations, such as POAPs or Verifiable Credentials. Negative attestations are attestations that a person is not incentivized to maintain or present. In the off-chain world, these would be credit default lists, criminal records, SDN listings etc.

In the web3 world, negative attestations can be as simple as having violations against the code of conduct for a DAO. A trivial example is a code of conduct that stipulates against the use of profanity, perhaps with a formal reference lexicon. A simple three-strikes rule can involve users losing membership to the DAO for repeated use of profanity on forums, as reported by other members. In this somewhat contrived example, the use of negative reputation is actually more inclusive than the use of positive reputation, which would require an individual to present proof of a history of having used “clean” language in order to join the DAO. The key difference though, is that negative attestations are usually issued without requiring the individual to consent to accept them (unlike Verifiable Credentials), and this is where it starts to become complicated and problematic.

From the individual’s perspective

Identity proofing and on-chain reputation is at the very core of how the interactions between separate discrete structures within the Mesosystem can both positively and negatively affect an individual.

Both in terms of KYC/AML, or reputation, the individual remains in complete control, either through self-custody or through legislation [3]. In all cases, it is the individual that must disclose proof of an on-chain address, or present a Verifiable Credential, or give consent for an IDP or data controller to share data.

The concept of the individual’s consent in Mesosystem interactions is a recurring theme. At the heart of this recurring theme of consent is the question of volition. If an individual is put at a relative disadvantage by not giving their consent, can it then be regarded as coerced consent?

If we begin to see the unconstrained proliferation of reputation systems in web3, we will likely reach a point of critical mass, whereby the individual gives their consent to share their data or on-chain histories. This could lead to the inadvertent development of web3 “social credit” systems, which we have seen can lead to homogenization in communities, and can stifle self-expression and experimentation.

Remember that in Bronfenbrenner’s model, influences are bi-directional. If individuals are motivated to maintain separate bifurcated identities and on-chain addresses and histories, this in turn will affect the design and architecture of our wallets and dapps, and it logically infers that there will always be open and permissionless DeFi protocols, as well as permissioned versions.

Exosystem

Again, referring to Bronfenbrenner’s definition of the Exosystem, these are the structures in which the individual does not participate, but that nonetheless have a concrete effect on the individual. In digital identity terms, we would consider technology trends or market dynamics.

The effect on the individual by structures within the Exosystem are amplified by the sheer size of these structures, and to get a sense of what this might look like, we can examine projections for market growth in Digital and Decentralized Identity technology.

Market Growth

There have been a number of attempts to estimate the Total Addressable Market for Digital / Decentralized Identity and its projected growth over the next number of years.

- According to a comprehensive report from IMARC group, the market for “Blockchain Identity Management” is estimated to grow from roughly $355.8 million USD in 2020, to about $21.8 billion USD by 2027.

- A report from Juniper Research [4] found that the decentralized identity sector will grow to reach an annual revenue of $1.1 billion USD by 2024.

- The McKinsey Global Institute [5] estimates that countries implementing digital ID could unlock value equivalent to 3% to 13% of GDP by 2030.

Decentralized Identity vs. Digital Identity

It is important to note though that “digital identity” does not necessarily mean “decentralized identity”, and the distinction is that many governmental digital identity platforms will be centralized.

In order to focus exclusively on decentralized identity solutions, we examined a report by Cheqd [6], which attempts to estimate the market within the web3 space. Their estimates suggest that the potential value of the web3 decentralized identity market is approximately $0.55 trillion USD.

Privacy, Fraud and Identity Theft

Another catalyst for the adoption and a potential proxy for gauging the size of the market, is looking at figures of fraud and identity theft, which we can assume will provide an incentive for organizations to explore innovations such as decentralized identity, that will lower risks and costs in this area.

The ID Theft Center (ITRC) reported that there were 1,862 reported data breaches in 2021. In their 2021 Business Aftermath Report they state that 58% experienced a “security breach or data breach or both”, of small businesses ( < 500 employees ) and that 44% of them paid between $250K and $500K USD to recover from a data breach. 42% of people for work for or own a small business have experienced a data breach involving their personal information, or have experienced identity theft.

From the Individual’s Perspective

The available research all suggests that digital identity will become increasingly ubiquitous in our daily lives. Decentralized identity and web3 will also see increased and widespread adoption. This suggests that the structures within the Exosystem will exert more and more influence over the lives of the individual over the coming years. The quality of the influence on the individual depends then on the nature of the structures within the Exosystem.

The Nature of Structures in the Exosystem

The core tenet of blockchain and web3 is that decentralized and permissionless systems can improve our governance structures and mitigate against abuses of the state and against surveillance capitalism. In this regard, the core values of web3 broadly align with the original Principles of Self Sovereign Identity [7]. However, Digital Identity, and even Decentralized Identity, does not always mean the same thing as Self Sovereign Identity.

As the concept of Digital Identity continues to evolve and see more adoption, the extent to which this will include technologies such as DIDs, Verifiable Credentials and DLT is yet to be seen. For example, it is possible to use DIDs without a blockchain, and it is possible to build an identity system using a blockchain which still falls short of the principles of SSI. Such a system can still have gatekeepers and guardians that can engage in censorship, or can abstract away the access to the underlying ledger behind APIs or custodial agents, or by being compatible with only approved closed-source wallets (see the EBSI as an example).

At a high level we can think of the the nature of individual structures within the Exosystem as falling somewhere in a multi-dimensional rubric of antagonistic characteristics:

- Permissionless <> Permissioned

- Centralized <> Decentralized

e.g. web2 vs. web3 - High Assurance <> Low Assurance

e.g. national passport vs. library member card - Open <> Closed

i.e. proprietary vs. open source software and/or standards

Obviously big tech surveillance capitalist companies will favor closed and highly centralized systems. For our purposes, let’s assume that centralized systems are all built on closed source software. In doing so, we arrive at a comparison matrix that can give us an idea of the extent to which Decentralized Identity technologies can be leveraged for different use cases.

As we can see from the above matrix, there is a trend towards more “high assurance” credentials being issued on permissioned infrastructure. Those such as Bright ID or Proof of Humanity offer permissionless and decentralized alternatives, but they have not seen the level of adoption that more permissioned versions have, such as Verified.me or Travel Pass. When we add in the level of adoption into the dataset, we can see that permissioned systems have thus far seen greater adoption:

The issue with regards to high assurance attestations / credentials, is the shift in the risk profile for sybil attacks. While it is possible to offer high assurance attestations in a permissionless (and thus censorship resistant) manner, it involves a trade off in terms of privacy.

In isolation, we can begin to observe how structures within the Exosystem start to evolve certain characteristics depending on what aspects of an individuals identity they relate to.

The Digital Identity Trilemma

One common model for understanding decentralized identity is referred to as the decentralized identity trilemma as described by Maciek Laskus[8]. This describes any given decentralized identity solution as having any two of three attributes, being permissionless, privacy preserving and sybil resistant.

Permissionless — anyone is able to create as many identities as they want to without permission from an intermediary, such as is the case with fully decentralized systems.

Privacy-preserving — users can create identifiers without having to reveal personally identifying information such as their real name etc.

Sybil-resistant — users cannot create multiple identities in order to appear as more than one person to a system or organization.

Lets take the simple example of a national ID card, issued as a digital ID, which is sybil resistant, and privacy preserving (except to the government obviously), but not permissionless, as only the government can issue.

In order to create a robust and dependable ID system that is fully permissionless, we need to look at concepts that rely on social graphs (or “webs-of-trust”). BrightID is an example of such a system. This system allows users to verify their identities by collecting attestations from their connections, which are people that they know. Connections have levels, which are “already know”, to “just met” to “suspicious”. As well as collecting attestations, users are expected to attest to other users, forming social graphs. From their documentation: “Your BrightID is verified based on the social relationships that you present with your connections”.

Proof of Humanity is similar in concept, in that it requires people to register and have other registered users vouch for them. Proof of Humanity also requires a monetary deposit as a form of sybil resistance mechanism, though this deposit can be crowdfunded from connections that a person already knows on the platform. The deposit is returned on successful registration.

Both systems are examples of designs that sacrifice privacy to some degree in order to remain sybil resistant and permissionless.

For this reason, many applications built on decentralized identity technology will be permissioned. There are also other forces, including influences from the Macrosystem, which will lead to more widespread use of permissioned systems, including legislation such as GDPR, CCPA etc. This legislation will increase the perceived risk of liability for entities that facilitate the writing of PII to an immutable public ledger. This will of course lead to permissioned ledgers with active censorship.

From the Individual’s Perspective

Relating all of this back to our ecological model, we can see that the nature and characteristics as well as the size of the structures within the Exosystem will have a material effect on the individual’s identity.

As applications and services within the Exosystem make decisions based on the various trade-offs described above, users may be forced to compromise on privacy or control or both, and depending on the individual’s, this may very well affect the structures in the Microsystem, in terms of which applications they use or which communities they engage with.

The extent to which certain structures occupy the Exosystem will have an effect on the extent of the individual’s choice. For example, the almost ubiquitous ReCAPTCHA system that many websites use to protect against bots can collect enough information that it could reliably de-anonymize and track many users [9] that simply wish to prove they are human to gain access to a service.

According to available market research, Decentralized Identity technology will see continued widespread adoption, but not as much as centralized technology systems. Even within the scope of Decentralized Identity, it is likely that we will see the prevalence of permissioned networks that are subject to censorship. The evidence does not seem to suggest the realization of the original concept of Self Sovereign Identity, or at least not to any significant extent.

On balance, this will have both positive and negative consequences for the individual. On balance, it will likely mean less bureaucracy, more efficiency, and more control and privacy. It will however, also result in even more control in the hands of governments and large corporations.

We’ve seen examples of when this sort of control is exerted against the interests of individuals for political purposes, for example with the Cambridge Analytica scandal, or when the Canadian government instructed banks to freeze accounts of protestors.

Macrosystem

The macrosystem defines the larger political and cultural context in which the individual exists, and structures in this layer have a cascading influence on the relationships between entities and structures on all other layers. In terms of digital identity, the most influential structures within this layer are government legislation, and societal attitudes and trends.

Government Legislation

Legislators are catching up quickly with new technological trends and development and putting in place comprehensive legislation to protect consumers privacy. The legislation that is most known for leading the way in this regard is the EU’s GDPR and subsequently California’s CCPA, but many other governments are enacting similar legislation. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [10], almost three quarters of countries have similar legislation:

The details within different acts of legislation may have various consequences for infrastructure providers with relation to identity data. For example, a core tenet of GDPR is the right-to-be-forgotten [11]:

“The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay”.

For this reason many decentralized identity ledgers such as Sovrin for example, created a permissioned network where anyone can read, but only approved parties can write.

Government and public sector initiatives

A number of countries have started National Identity Documents as Digital IDs as opposed to the traditional card and plastic versions. There are now over 25 countries worldwide that issue national IDs as digital credentials.

Even though a number of countries that adopt national digital identification schemes do so in a centralized manner, it is a big step towards decentralized identity, in that it promotes the use of credential wallets and digital authentication and certification etc.

The chart below shows the percentage of adoption of National Digital IDs that are issued and presented via a mobile app.

Currently, there are 14 countries in the EU that offer digital identity under the eIDAS regulation, but adoption is varied among countries, however the EU is targeting 80% of citizens to have a digital ID solution by 2030.

There are also a growing number of countries that are issuing digital driver’s license using the ISO 18013–5 mDL standard.

Societal Attitudes for Privacy and Control of Personal Data

Individuals are becoming far more active in terms of how they respond to their concerns over potential mishandling and misuse of their data. The below data comes from a survey conducted by Cisco in June 2021, of 2600 adults in 12 countries.

Breakdown of respondents that are concerned and have taken action over privacy:

I care about data privacy

86% I care about protecting others

I want more control

I am willing to spend time and money to protect data

79% This is a buying factor for me

I expect to pay more

47% I have switched companies or data providers over

their data policies or data sharing practices

Types of companies Left by Privacy Actives

This signifies a growing trend toward the concern over privacy and control of personal data turning into measurable action by consumers. This leads us to the question as to whether this trend represents an addressable market for products and services that offer privacy and control of personal data, such as those based on decentralized identity technology.

One such indication is a 2019 report from Pew Research [12], that found that US consumers are “somewhat more likely to favor better consumer tools than stronger laws to help safeguard personal data”, as shown in their survey:

55% — Better tools for allowing people to control their personal information

44% — Stronger laws covering what companies can with people’s data

This data would suggest that consumers are more aware of privacy issues, and are more motivated to adopt tools and technologies that would afford them more privacy and control. This is in stark contrast with data from 2015, that shows substantially less awareness or concern around the same issues.

That being said, it is still unclear as to the level of awareness of the available privacy tools and technologies. A survey from Deloitte [13] concluded that many consumers aren’t aware of their options. When survey participants were asked “which of the following steps have you taken to protect your data during your online activities”, these were the responses:

From the Individual’s Perspective

Despite the evidence of consumers taking action against companies that they perceive to abuse their personal data, we are yet to see significant adoption of privacy enhancing technologies.

There could be several reasons for this phenomenon, including a lack of awareness of the availability of privacy preserving technologies, and inability to escape the network effects of Facebook, Google etc. However, one common theory that has gained widespread recognition is that of the privacy paradox [14]. In this theory, consumers are shown to care deeply about their individual and collective privacy, but fail to be motivated to take significant action to protect it, choosing instead to prioritize convenience and ease of use of privacy in almost all cases.

If this is the case, then it follows that as web3 technologies become easier and more convenient to use, we will see more adoption of web3 technologies to facilitate this transition to a form of digital identity that affords more control and agency to the individual, empowering them to grow, explore and build.

From a socio-ecological perspective, the increasing trend of individuals moving to more privacy enhancing or self-custody products, illustrates the sort of bidirectional interrelationship between the various layers of the ecosystem that affects both the individual and the broader ecosystem as a whole. In Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, there are bi-directional influences that have impact in two directions, both away from the individual and towards the individual, resulting in an individual that is affected by the ecosystem in which they inhabit, and an ecosystem that is co-created by individuals.

Summary

- Digital Identity is becoming more of a factor in everyday life, individuals will rely on credential wallets on their devices to interact with their local and online environments.

- Decentralized identity technology will see more widespread adoption, though it is unlikely we will see the full realization of the principles of self sovereign identity, except for some use cases.

- The more interactions and relationships there are between separate structures of the Microsystem, (online accounts and on-chain assets and activity) the more the effects on the individual become greater than the sum of parts.

- An individual’s identity is dynamic and contextual, and there will always be a tension between censorship resistance, sybil resistance and privacy. The systems we have designed are not sufficiently complex to allow a person to fully manage their digital identity properly, and will likely require some insights from social sciences to develop further.

- Once we identify emerging trends within any one area of the ecosystem, we can use an ecological framework to follow the paths of influence to identify where effects in other parts of the ecosystem will appear next.

- By examining the size of structures in each layer relative to the other structures in that layer, we can ascertain how they will have an effect on the lower layers and will affect an individual’s freedom of choice.

- Influence between layers of the ecological model is bidirectional. When examining emerging trends or innovations, we can use this insight to look for potential reciprocal or reactive influences in the future, (e.g. excessively controlling legislation pushes people to adopt privacy technologies, which has the opposite effect the legislation intended).

Conclusions

By adapting Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Framework for Human Development as a model for understanding the evolution of digital and decentralized identity, we can start to develop a framework for identifying future trends.

Bronfenbrenner’s framework is useful because it puts the individual at the center, but it also reminds us that the ecosystem that the individual inhabits is also shaped by the individual. There are multiple layers of influence being exerted on us as individuals, and our behavior in response to those influences exerts equal and opposite influence on aggregate. This result is a complex and dynamic ecosystem that is in continual flux.

In understanding this basic principle, we begin to see why the concept of decentralized identity is so difficult to design for, and why sometimes the most powerful technology fails to see adoption or simply doesn’t find any real use cases.

As architects, developers, product managers etc. we can use frameworks like Bronfenbrenner’s to help us understand where the edges are, where we can find use cases that fulfill the individual’s needs. As structures change and evolve in each layer, the effects cascade and reverberate. This can allow us to make educated guesses about what sort of technology will see adoption, and when, and for how long, before things change again.

Concrete examples include predicting which standards will see widespread adoption, e.g. will we see more adoption of DIDs and Verifiable Credentials vs. the use of SBTs, or to understand which decentralized networks may see more adoption.

Another example can be in terms of how we use reputation systems, how we harness our collective intelligence in ways that are resistant to manipulation, but doing so in ways that don’t inadvertently become exclusive or promote homogeneity.

We can model the behavioral patterns of pluralistic, intersecting communities of individuals in ways that can help us make decisions about designing governance systems for DAOs. For example, Buterin et al. describe a possible approach to governance in their paper: Decentralized Society: Finding Web3’s Soul [15]:

“DAOs susceptible to majoritarian capture could compute over SBTs to bring maximally diverse members together in conversation and ensure minority voices are heard”.

Many of us have wondered and speculated as to why the vision of decentralized identity as “blockchain’s killer use case” still remains a prospect rather than a reality. It could be simply that our collective understanding of the nature of the relationship between identity and technology is deepening and maturing. Self Sovereign Identity and Decentralized Identity contain solutions that were largely contributed by computer scientists. We are beginning to see now that we need more contributions and insights from the fields of social sciences, where the dynamic nature and complexity of human identity has been grappled with for decades.

Works Referenced

[1] U. Bronfenbrenner, The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press, 1979.

[2] European Commission, “Commission proposes a trusted and secure Digital Identity for all Europeans”, 03-Jun-2021. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_2663

[3] A. John, “Can less be more?,” CyberForge, 11-Apr-2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.cyberforge.com/can-less-be-more/. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[4] J. Moar, “Self-sovereign identity to be a billion-dollar industry by 2024, but monetisation will remain a Stru,” Self-Sovereign Identity to be a Billion-Dollar Industry by 2024, Feb-2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.juniperresearch.com/press/self-sovereign-identity-to-be-a-billion-dollar. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[5] O. White, A. Madgavkar, J. Manyika, D. Mahajan, J. Bughin, M. McCarthy, and O. Sperling, “Digital identification: A key to inclusive growth,” McKinsey & Company, 28-Jan-2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/digital-identification-a-key-to-inclusive-growth. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[6] F. Edwards and E. Yumasheva, “Self-Sovereign Identity: How big is the market opportunity?,” 09-Mar-2022. [Online]. Available: https://cheqd.io/self-sovereign-identity-market-opportunity-report. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[7] C. Allen, “Self-sovereign-identity/self-sovereign-identity-principles.md at master · WebOfTrustInfo/self-sovereign-identity,” GitHub, 23-Oct-2016. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/WebOfTrustInfo/self-sovereign-identity/blob/master/self-sovereign-identity-principles.md. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[8] M. Laskus, “Decentralized identity trilemma,” Maciek Laskus’ Blog, 13-Aug-2018. [Online]. Available: https://maciek.blog/dit/. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[9] Wikipedia contributors, ‘Privacy concerns regarding Google — — Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia’. 2022.

[10] “Data Protection and Privacy Legislation Worldwide,” UNCTAD, 14-Dec-2021. [Online]. Available: https://unctad.org/page/data-protection-and-privacy-legislation-worldwide. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[11] B. Wolford, “Everything you need to know about the ‘right to be forgotten,’” GDPR.eu, 24-Apr-2020. [Online]. Available: https://gdpr.eu/right-to-be-forgotten/. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[12] S. Atske, “Americans and privacy: Concerned, confused and feeling lack of control over their personal information,” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 17-Aug-2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-and-privacy-concerned-confused-and-feeling-lack-of-control-over-their-personal-information/. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[13] B. Auxier, D. Jarvis, and I. Bartoletti, “The consumer data privacy paradox: Real or not?,” Deloitte Insights, 23-Mar-2022. [Online]. Available: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/technology/consumer-data-privacy-paradox.html. [Accessed: 06-Jan-2023].

[14] S. Barth and M. D. T. de Jong, ‘The privacy paradox — Investigating discrepancies between expressed privacy concerns and actual online behavior — A systematic literature review’, Telematics and Informatics, vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 1038–1058, 2017.

[15] Weyl, Eric Glen and Ohlhaver, Puja and Buterin, Vitalik, Decentralized Society: Finding Web3’s Soul (May 10, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4105763 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4105763

[16] M. Vizcarrondo Oppenheimer, N. Velez Agosto, and J. Soto, ‘Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory Revision’, 11 2017. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321012999_Bronfenbrenner’s_Bioecological_Theory_Revision