by Javier Paz

Big cryptocurrency exchanges are not necessarily averse to accountants or strict audits, but those that have something to hide are easily able to avoid the kind of review that would have brought the problems of FTX Trading and its affiliates to light before their catastrophic failures last month.

Forbes identified the world’s 50 largest exchanges late in August, only weeks before the FTX crisis unfolded, and half of them agreed to share data about their audit practices. Of the participants, 16 revealed their books were audited, and of those, half went with the Big Four accounting firms–Deloitte, PwC, Ernst & Young and KPMG–and one firm, Binance, has since reportedly disclosed to the Wall Street Journal that Paris-based Mazars is auditing its reserves. Along with being the biggest, the Big Four are arguably the best, at least according to Accounting Today’s 2021 rankings of U.S. audit and accounting firms, which measure the firms’ revenue to determine the standings.

Depending on where they are based, cryptocurrency exchanges do not have to submit to audits. If they do, their financial statements can remain private or be shared only with regulators. This is in stark contrast to issuers of publicly traded securities in major developed markets whose accounts must be regularly audited and made public.

For firms posing a high reputational risk, Big Four firms may discreetly turn down an auditor job but then serve as consultants for a few years. If the accountants become sufficiently comfortable, they will then take on the auditing. Lower ranked accounting firms, sometimes with less pristine records than those at the top, could have fewer qualms about taking on higher-risk firms as auditing clients.

The crypto exchanges reviewed by the Big Four included CME GroupCME +0.5%, Coinbase (COIN), Bitstamp, Gemini, and Bittrex in the U.S., LMAX from the U.K., Bitbank of Japan and South Korea’s Upbit. These exchanges are not the largest by trading volume nor do they have the most crypto products. However, they run their respective crypto businesses with more transparency than many of their competitors and tend to share the standards of highly regulated financial firms. The remaining eight exchanges used lower-profile accountants.

In the case of FTX, Prager Metis International (47th on the Accounting Today list) audited the parent company and Armanino (21st) the U.S. subsidiary. FTX’s auditor picks weren’t a red flag merely because of the low rankings but because their signed audits meant little more than the Excel balance sheet that a non-accountant FTX person generated and which was reviewed by the Financial Times when FTX’s Bankman-Fried was seeking fresh capital to avert a bankruptcy filing.

According to Francine McKenna, a lecturer at Wharton who has said she reviewed the FTX audited statements from Prager Metis and Armanino, the two accounting firms working for the exchange did not issue letters stating the companies’ internal controls were adequate, as is customary. Furthermore, these firms took on auditing jobs under terms that presumably kept them from seeing the full picture of FTX and Alameda holdings, something necessary to evaluate the propriety of related-party transactions.

Binance’s recent choice of Mazars Group to verify its reserves, if proved to be true, would be a noteworthy first step toward the right type of disclosure for a firm notorious for keeping its financial condition and inner dealings secret. It also invites scrutiny of the auditor itself. Besides Binance, Mazars are the auditor of Luno and BingX. The Accounting Today ranking places Mazars USA as the 26th-largest firm but going by 2021 global revenue, the Mazars group generated the equivalent of $2.48 billion, which Forbes estimates puts the French group in the number 8 position.

An August 2022 regulatory audit of Mazars USA revealed shortcomings that call into question the firm’s credibility performing asset reserve audits that tens of millions of Binance clients will rely on as accurate. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), the U.S. accounting regulator that carries out periodic audits of auditors themselves, found that Mazars “did not identify and test any controls over the valuation of certain assets” and relied too much on owners’ representations and screenshots of asset valuation system settings instead of verifying if these settings had changed over time. As part of their evaluation, the regulators reviewed two 2021 Mazars audits and two from 2019, revealing significant deficiencies–technically called Part I.A deficiencies-in all four audits.

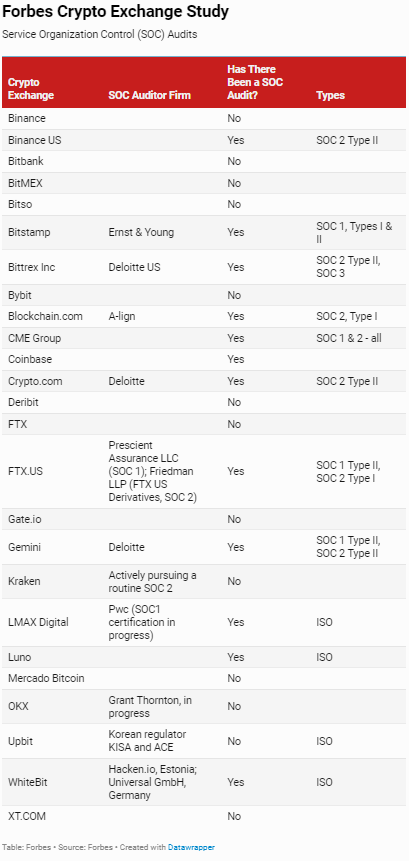

Additional Audits

The exchanges Forbes surveyed also provided details regarding exchanges’ Service Organization Control (SOC) audits, and the names of firms doing these more specialized audits. SOC audits may not be useful for the millions of small crypto investors, but they are a must-have for institutional investors to determine if an exchange would be a trustworthy trading counterparty. These certificates attest that a firm is taking good care of cybersecurity and data protection. Other exchanges go as far as getting an ISO certification after an arduous process of validating competence to a qualified third party. The bottom line with SOC audits is that if an exchange attracts institutional investors, that tends to enhance the liquidity and tight spreads that retail investors receive. The Forbes survey also revealed that FTX did not have a SOC audit and was hoping to get these certificates in Q4 2022 or Q1 2023 from Prescient Assurance LLC, but given the firm’s collapse in November, it is unlikely they got them or will do so.

The FTX collapse and the ensuing contagion have made an emerging topic–proof of reserves (PoR) attestations–pick up serious steam. The original list of exchanges getting PoR and the firms with this specialized auditing reserves are these:

Gate.io. Armanino LLP – Assets and liabilities audited by third party firm

Kraken. Armanino LLP – Assets and liabilities audited by third party firm

BitMEX. Assets proof of reserves only. BitcoinBTC -0.3% proof of reserves & proof of liabilities explorer – no known external auditor

Luno. Assets proof of reserve only. Luno informed Forbes that Mazars South Africa, part of Mazars Group is its auditor and is charged with performing quarterly proofs of reserves

New proofs of reserves announced:

Binance. Proof of reserve showing the assets side and auditor-assisted, but not sufficient clarity on whether the liabilities side will be included or the extent of audit/attestation. CEO Changpeng Zhao (CZ) tweeted on November 8 that Binance “will start to do proof-of-reserves soon. Full transparency.” Earlier this week, CZ communicated that Binance’s auditor (now identified as Mazars) asked the exchange to move large sums of money to new addresses and thus demonstrate control of the assets.

OKX. Proof of reserves showing the assets side, not the liabilities side nor the name of the auditing firm (if any). OKX tweeted on November 10 that it was prioritizing a cryptographically verifiable method (Merkle proof of funds, Merkle POF): “For #OKX, transparency, risk management, & consumer protection come first. We’re hiring an auditor & will publish an auditable Merkle POF asap. Here are 23 BTC addresses (~69K BTC) & 13 ERC20 addresses (~$2+ BN) as 𝗽𝗮𝗿𝘁 of our reserves for users to verify.”

KuCoin. Proof of reserves showing the assets side, not the liabilities side nor the name of the auditing firm (if any). The firm’s CEO Johnny Lyu tweeted: “Protecting user funds is the top priority at KuCoin. We will release Merkle tree proof-of-reserves or POF in about one month.”

Huobi. The firm announced concurrently its reserves and wallet information and that it was under new management, acquired by About Capital on November 13, a reflection of the financial straits of exchanges these days.

BingX. The exchange communicated to Forbes this month that it completed a Merkel tree proof-of-reserves with the assistance of auditor Mazars.

A Profession At A Crossroad

Financial auditing is a practice that people of a certain age assure me used to mean something. Over the past two decades, there’s been more than a handful of high-profile cases of auditors asleep at the wheel where their clients–the likes of Enron, Bernie Madoff Investment Securities, MF Global–got away with massive frauds, reaching into the billions of dollars. FTX just happens to be the latest.

To some venture-capital icons like Temasek and SoftBank, financial audits during the last few years seem to me to have been niceties, evidenced by the eight-to-nine-figure checks they wrote to FTX and other hot startups, apparently without demanding financial audits or verifying internal controls.

As willing participants in a crypto-fueled investment frenzy of the past two years, these wealthy firms with all the talent and know-how to invest more efficiently than retail investors repeated the mistakes of the WalmartWMT +1.3% heirs and Rupert Murdoch at Theranos a few years earlier, losing most if not all of the capital invested. Temasek wrote off the full $375 million it invested and Softbank’s Vision Fund reported investment losses of $9.75 billion during the three-month period ending in September and which included an FTX write down of less than $100 million.

Missed Auditor Red Flags

An auditing-related red flag takes different forms, such as when an audited firm replaces a higher ranked auditor with a lesser ranked one or when it terminates an auditor relationship without announcing a new auditing firm. In both of the previous scenarios the message is clear: What might have the auditor learned or said that led to their recusal from the job? The fact that more than 30 of the top 50 exchanges don’t seem to have an audit period is also a red flag for investors – it should be reasonable to assume that there is some major reason for them not having that type of credential.

Assuming that auditors’ work still matters and is one of the best ways the public has to pick up signs of trouble at the larger crypto exchanges, why didn’t the alarm bells ring out with regards to FTX?

Firstly, auditors not feeling comfortable signing off on a client’s audit can recuse itself, something that generates a discrete red flag. Secondly, a Big Four firm taking on a crypto exchange means that the former sees the client relationship as a manageable reputational risk – a green flag for investors. Forbes research revealed last month that two Big Four firms – Deloitte and PwC – acted in a consulting capacity to FTX but not as the firm’s auditors – a red flag for investors. More importantly, the signs of FTX doing something that auditors couldn’t sign off were there, but no one picked them up sufficiently because the industry remains young and has not adopted formal ways to gather key performance indicator data nor do traditional regulators require it.

The ranking alone of the auditing firm does not necessarily condition the quality of its work, something that is apparent as one reviews the work of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) – the U.S. accounting regulator which carries out regular audits of auditors themselves. Besides the low 2021 revenue ranking, Prager Metis and Armanino earned low PCAOB reviews prior to the FTX relationship.

Armanino. 2019 PCAOB audit of two of Armanino audits. “One of the deficiencies identified was of such significance that it appeared to the [PCAOB] inspection team that the firm, at the time it issued its audit report, had not obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence to support its opinion that the financial statements were presented fairly, in all material respects.” The Board went on to say “in this audit, the auditor issued an opinion without satisfying its fundamental obligation to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements were free of material misstatement.”

Prager Metis CPAs, LLC. A 2020 PCAOB evaluation of four of Prager Metis’ 2019 audits led the regulator to conclude that Prager Metis audits were at a “heightened risk of material misstatement.” The audit report indicated that Prager Metis at the time had 40 clients and only 5 total engagement partners involved on issuer audit work, meaning they had relatively short amount of time with each client firm. “We believe the firm, at the time it issued its audit report(s), had not obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence to support its opinion on the issuer’s financial statements and/or ICFR” – this last point stands for internal control over financial reporting.