And say goodbye to keyword based search

While GPT 3+ or ChatGPT, prompt engineering is easier to understand intuitively. With many guides and examples available on the web, and social media. Such as

- https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6654000-best-practices-for-prompt-engineering-with-openai-api

- https://github.com/f/awesome-chatgpt-prompts

Embeddings, requires programming, and are less understood, due to various counter intuitive behaviour on how it works. But, is an extremely powerful tool for search, or to be used together with existing text-based models, for various other possible use cases.

Embeddings is arguably an equally powerful tool, within the AI toolkit, for instruction models. Due to its ability to handle searches across different words and sentences, or even entire languages. Focusing on searching for the relevant document, for any query.

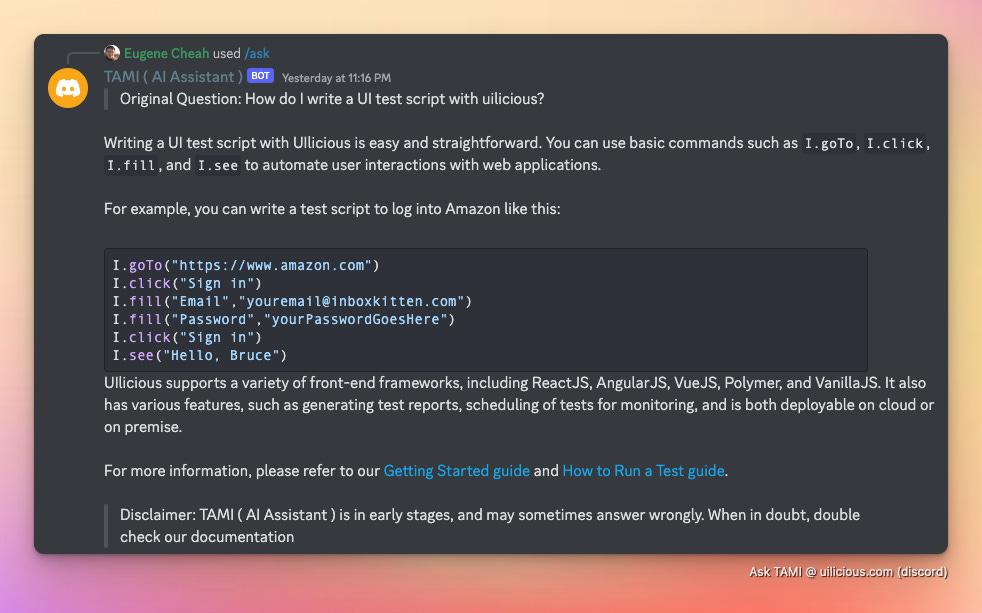

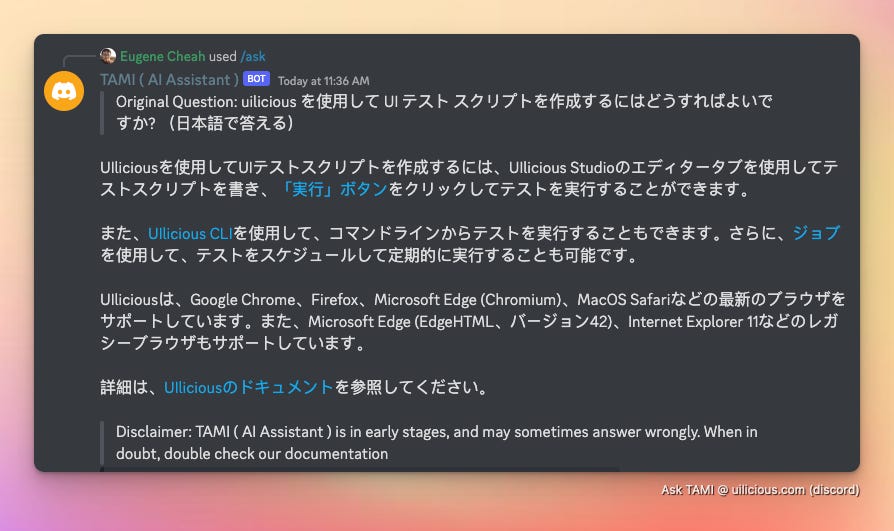

For example, it can be used to power searching and answer from an English-based documentation. In English …

Or Japanese …

Or any other languages that the AI model supports. Embeddings can also be used for other tasks such as question-answering, text classification, and generating text.

Note that this article focuses on the search aspect, the answering process is in a follow-up article.

What is an embedding vector?

To generate an embedding vector, one will use an embedding AI model, which converts any text (a large document, a sentence, or even a word), into an “N dimension array”, called a vector.

For example a sentence like How do I write a UI test script with Uilicious?

Can be converted into the following array (called a vector) via OpenAI text-embedding-ada-002 model: [0.010046141, -0.009800113, 0.014761676, -0.022538893, ... an a 1000+ numbers]

This vector represents the AI model’s summarized understanding of the text. This can be thought of as an “N-word summary” written in a language that only the AI can understand.

Where related documents will have a close distance from each other, based on the AI’s understanding of the document (and not its text). This is a major leap beyond the simple keyword searches of classic search engines, as it can handle variations in sentence structure and language (provided the AI model is trained to understand said language).

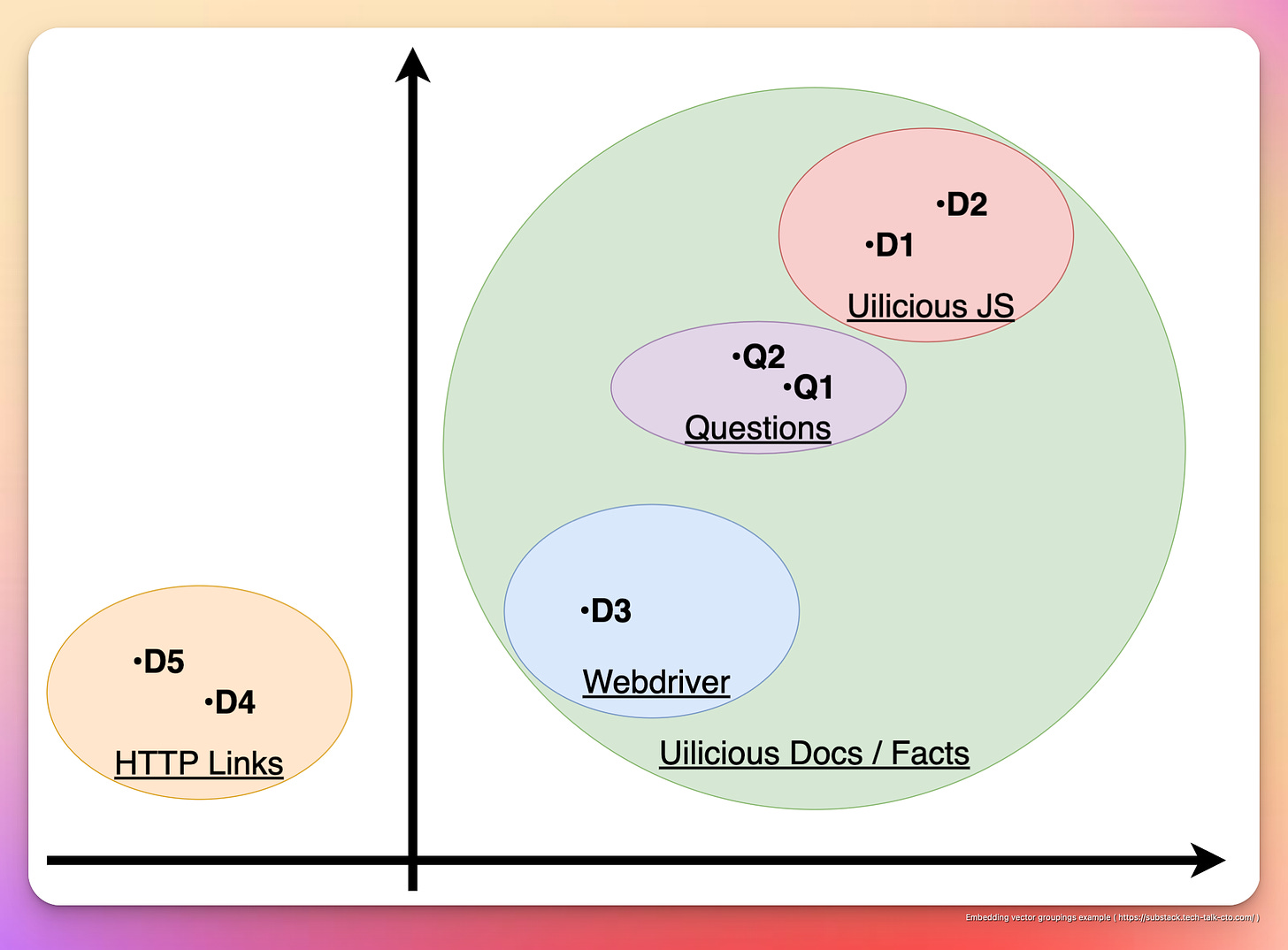

Take the following as a hypothetical example, oversimplified inaccurately into 2 dimension space so that it is easier to understand:

Which can be visually presented as the following in 2D space.

For example, D1,2,3 are all documents related to how to use Uilicious in various ways and are grouped together in one cluster

D4 and D5, being simply links and having no inherent value beyond that, are grouped separately in another cluster.

Furthermore, D1 & D2 are further grouped together, as they are about Uilicious testing commands, using our very own JavaScript-based testing language.

While D3 is grouped separately, as it is regarding using the web driver protocol on our infrastructure directly, which is intended for a different use case and audiences.

Similarly, for Q1 and Q2, despite the drastic differences in sentence structure and language, because it is essentially the same question, the two questions are grouped together. Additionally, while the question could technically be interpreted both ways (using Uilicious test script, or webdriver protocol), because the question implies the usage of Uilicious test scripting over webdriver, its location is “closer” to D1 & D2, and further away from D3.

As such, despite having huge overlaps in keywords, these nuances in groupings are captured by the AI encoded within the embeddings.

In reality, however, instead of an oversimplified 2 dimension array which is easy for humans to understand, an embedding can easily be a 1,000+ dimension array. This array is unique to the specific AI model used, and cannot be mixed with another AI model’s embeddings.

Math notes: N-dimension math is not compatible with 2/3D math

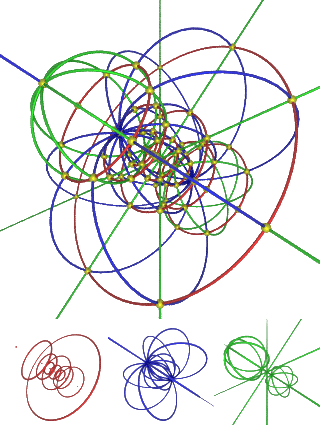

While the oversimplified 2 dimension examples, are good for understanding the high-level concept of grouping relatively to one question (or one point of view), it does not accurately represent an N-sphere, which is the mathematical construct used to describe a space of N dimensions.

Due to complicated N dimension math, you can have situations, where A can be close to B, B can be close to C, but A and C can be considered far from each other. Which is an extremely counter-intuitive gotcha.

This is known as the Curse of Dimensionality

Such distances are only useful when used relative to the same point, and the formulas used. Which can be calculated either using

- Euclidean distance: also known as Pythagorean Theorem on steroids, it is the most common distance metric used and is the straight line distance between two points in N-sphere.

- Cosine Similarity: it is a measure of angular distance between two points in an N-sphere, and is useful for measuring the similarity of documents or other vectors.

- Manhattan or Hamming Distance: these two metrics are used to measure the differences between two vectors, and are useful for measuring the “edit distance” between two strings.

While the effectiveness of each formula has their respective pros and cons, for different use cases. For textual search, it is generally accepted that Euclidean distance “works better” in most cases, and “good enough” for cases where other methods edge out.

All of which, is used in effect to reduce N-Dimensions, to a single dimension (distance), relative to a single point. This as a result, would mean groupings can / may change drastically depending on the question asked.

This “relativity” nature of distances, makes classic database search indexes ineffective.

If that makes no sense, this is how 4 dimension space is visualized properly with math N-Spheres.

Now imagine 1,000 dimensions? Yea it makes no sense.

So without derailing this topic with a PHD paper, I will summarise this as just trusting the math professors.

All we need to understand is that in general, the closer the distance is between two vector embedding points, the increased likelihood they are relevant to each other.

From a practical implementation standpoint. Start with using Euclidean distance first. Before considering using the other formulas which are fine-tuned for better results through trial and error for your use case (not recommended).

Searching embeddings with a vector database

So given that we can convert various documents into embeddings, we can now store in within a database and perform a search with it.

However, unlike an SQL database searching with text, both the search and the data being searched are the vector embedding itself. This means that traditional database search indexes are ineffective when it comes to searching for embeddings.

We can have all your documents embeddings, precomputed, and stored into a vector search database. Which can then be used to provide a list of matches, ranked by the closest distance.

This can be done using existing vector databases such as

- REDIS: a popular open-source database that can be used to store vector embeddings and search them efficiently.

- Annoy: a library created by Spotify which uses an optimized algorithm to search embeddings quickly.

- FAISS: a library created by Facebook which provides efficient search algorithms for large datasets.

One major thing to note, vector search “database tech” is relatively new. Where a large majority of the vector search databases were designed for use cases found in companies like Facebook, Spotify or Google, with record sets in the size of millions or billions. And may not be optimised for small datasets.

This is going to be a constantly changing field in the next few years, here is a github ‘awesome-list’ to help track and find future vector search databases

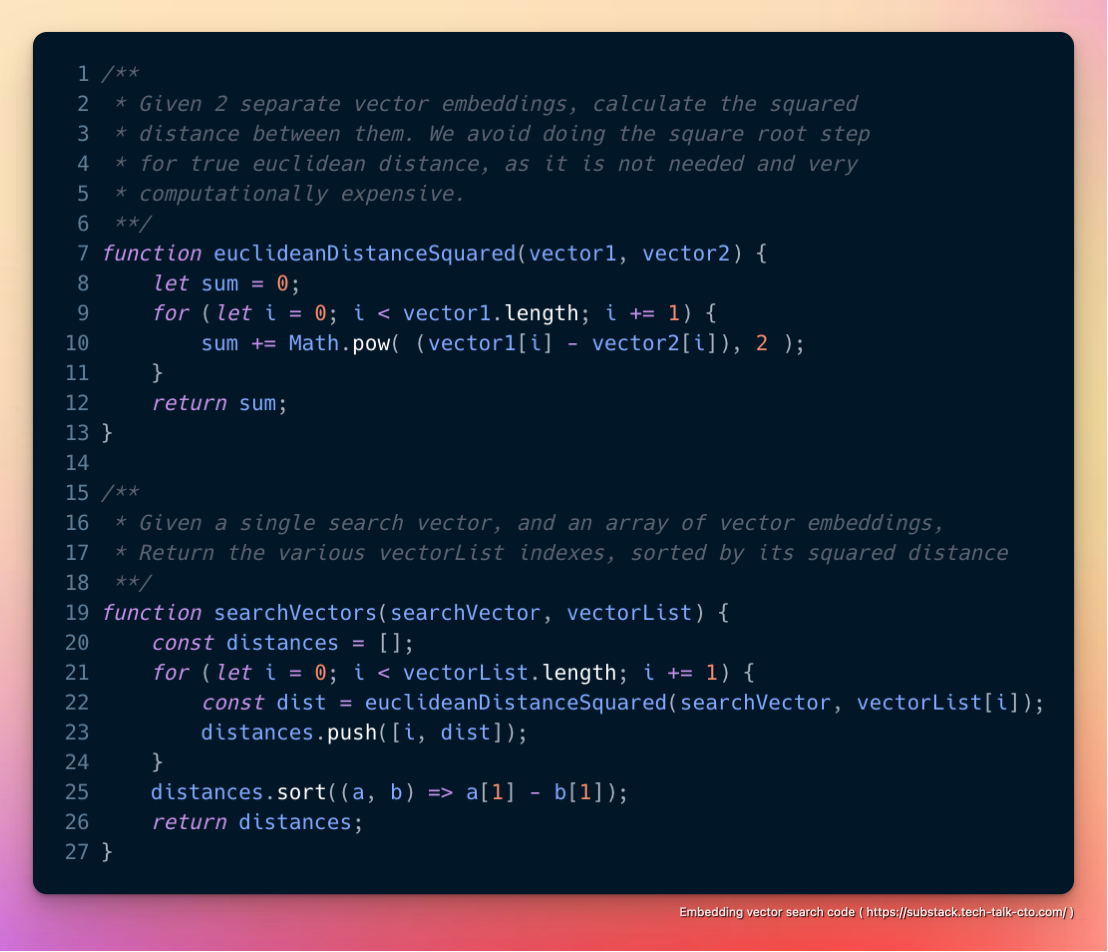

As such, in general, we found for small datasets of (<10,000 ~ 100,000 embeddings), keeping the embedding dataset in memory and brute-forcing euclidean-distance-squared is “good enough” for many use cases, and will sometime outperform formal database solutions (which will have disk/network overheads) with something like the following.

The obvious downside to this approach is that the entire dataset must be small enough to fit into memory without the overhead.

Regardless if you are using local in-memory embedding search, or a formal vector search database.

That’s it!

Embedding search is just a sort and rank algorithm that works flexibly with various languages, and scenarios. The question for you as the reader is how you can use it. It can be used as it is as a possible google search replacement, or together with other tools, from chat, to games. The possibilities are endless and open to exploration.