On algorithms and monoculture

A few weeks ago, I came across an excellent essay in LIFE Magazine titled The Emptiness of Too Much Leisure that summarized a key concern in the 1960s: automation resulting in a shorter working week. Everyone, the government included, was scrambling to fill the imminent idle time. As if doing nothing, resting, or being bored isn’t an activity itself.

With an average 7 hours of daily screen time spent consuming content and playing games, idle time is now filled with entertainment. The consumption is both work and leisure. Some people create content while others support them by subduing to algorithmic wonderlands. Society has become primarily entertainment-based. The subsequent result, if cultural critic Neil Postman was right, is the degradation of idiosyncratic and critical thinking.

We’ve progressed from social graphs to interest graphs to powerful AI models like GPT-3. Recommendation algorithms were certainly influential before, but recent advances in AI have made software exponentially powerful.

“For You”

When I think of AI products, TikTok immediately comes to mind. I think about how influential the For You algorithm is, how the app has its own policies and questionable moderation, how its employees can decide who goes viral …

Mostly, I think about how users get stuck in their own echo chamber of content that’s driven by their own behaviors—but, are they really? I’m a resident in the TikTok rabbit hole and I’ve noticed that certain editing styles, ways of storytelling, and aesthetics are standard. All seemingly new ideas converge into a standard or a fleeting trend. Consider that people’s mimetic desire is compounded by a meticulously designed algorithm; though TikTok is said to be more authentic than Instagram, at some point, the platform suppressed content from users it deemed “unattractive, poor, or otherwise undesirable.” It’s twisted, but the content creators who are the most desirable or meet a certain standard are at the forefront and are the product.

Platforms motivated by profit seem to have a similar veneer—the promise of self-expression. There’s a belief that TikTok promotes differences and subcultures because the For You page is personalized. Sure, you’ll see videos from a variety of niches but you don’t really tell TikTok what you want to see, it tells you. You can choose to engage or not. Either way, virality is determined by the sum of engagement from other users with similar interests.

1 It’s consensus; everyone has to agree the content is funny or cool or educational or whatever. The positive? Shared consciousness. The problem? The return of the mainstream and exclusion of fringe ideas.

For example, shared consciousness on #Booktok means people suggest the same five books, often something written by Colleen Hoover, which helped her sell more books than the Bible in 2022. Return of the mainstream means the same author, Hoover, held 6 of the top ten best seller spots on the New York Times paperback fiction list in 2022.

Monoculture

What if we mirror a similar scenario in products like ChatGPT or Artifact, the upcoming AI news app from the Instagram founders?

“These systems are a reflection of a collective Internet. People put their ass out there and this thing scours them in such a way that it returns the generic average. If I’m going to return the generic average of a murder mystery, it’s gonna be boring.” — Ben Recht, Could an A.I. Chatbot Rewrite My Novel?

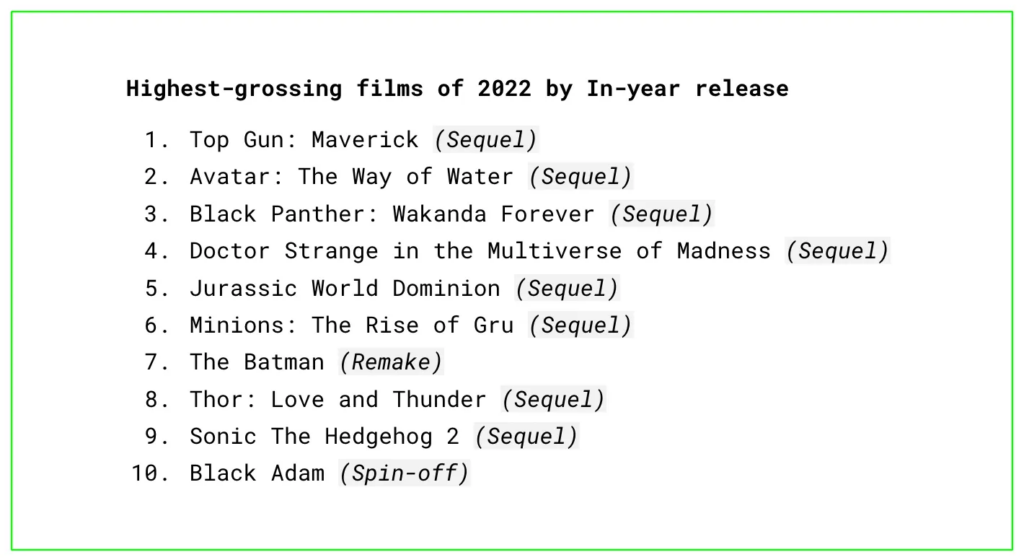

Gone are the days of scouring Wikipedia or reading books to create a cogent argument or opinion … And, who knows if we’ll still use “Googling” as a verb. People can feed ChatGPT the same prompt and get a book summary, create a recipe, or fix code. Humans will have superpowers, armed with a suite of AI apps (we’ll dive into this in part 2 of this essay). I think we’ll collectively put too much trust in these products, even though we shouldn’t. In the end, everyone will have the same writing tone, visit the same places on holidays, listen to the same music, keep watching superhero movies, and so on. This is already happening—just look at coffee shops around the world, Marvel’s box office dominance, and today’s music production. Social media introduced monoculture by the people for the people. With AI, it’ll only get more pronounced.

Monoculture has typically been tied to physical or time-bound presence, but for a generation that lives on the internet, shared consciousness means shared interests resulting in viral, consensus-driven content that exalts popular tastes and behaviors, and the cycle continues. Asynchronicity can be the default today because data is forever and can be shaped, algorithmically, into popular themes that bring familiarity online and offline.

Maybe if powerful AI models were public goods instead of private products, things would play out differently. Ultimately, the incentive structures exist to drive growth and revenue, meaning standard, or popular, content will prevail. This environment will push different perspectives further into the fringes, particularly those that break policies; this can be ethical, but can also be a disservice to the marginalized. Curators, cultural critics, and domain experts can sustain subcultures but I think artists and heretics might save us all. After all, the machines need new ideas to feed from.

Stay tuned for part 2, a deeper exploration into work and leisure in the age of AI.